When the ‘rescuer’ in the drama triangle gets fed up, there are problems ahead

25 May 2021

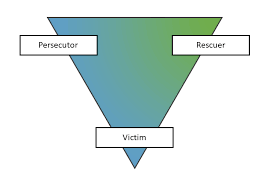

There is a model of relationships called the ‘drama triangle’, in which individuals move between the role of rescuer, persecutor or victim. In many relationships partners gravitate towards one of these roles - typically rescuer or victim.

By rescuer I mean someone who take a lot of responsibility for their partner, who gives them advice and who often adopts a slightly superior position.

But the drama triangle isn’t much fun for couples. It’s not that enjoyable feeling like a victim in your relationship, or a rescuer for that matter. Least of all do we want to feel like a persecutor and yet that’s how our partner may sometimes perceive us.

The way it often works is that partner A tends to take a lot of responsibility for the relationship and for the other person. Partner B, meanwhile, may often find that life is too much and they can’t cope with all the stresses and so they lean on partner A for support. This is the classic rescuer/victim dynamic.

The way it often works is that partner A tends to take a lot of responsibility for the relationship and for the other person. Partner B, meanwhile, may often find that life is too much and they can’t cope with all the stresses and so they lean on partner A for support. This is the classic rescuer/victim dynamic.

Either of these partners can become the persecutor. For example, when the rescuer feels frustrated and begins to criticise or when the victim gets fed up with feeling controlled and hits back with resentment or withdraws emotionally, leaving the other partner feeling abandoned.

Often what brings this kind of couple to therapy is when the rescuer gets fed up with taking so much responsibility for the relationship. Change can also be forced if the victim has had enough with feeling controlled.

Relationship therapy is an opportunity for the couple to look at the roles they have unconsciously taken on - roles that may have worked at one stage but have now become rigid and limiting.

Part of this may involve looking at how childhood experiences may have contributed to these roles. For example, as psychotherapist Robert Taibbi* points out, the rescuer is often an eldest or only child, or grew up in a chaotic family with few buffers between them and the parents.

As a child the rescuer learned that they needed to be ‘good’ and do what others wanted. As a result the rescuer is often disconnected from their own needs and tries to avoid conflict.

In couple therapy part of the process may be to help the rescuer realise that he or she does not need to take so much responsibility for the other person. Rescuers tend to think that they must ‘fix’ their partner’s problems, make them happy.

As the rescuer allows themselves to not get so involved in their partner’s life, their partner feels less controlled. The rescuer can also begin to express their own needs and wants in a more appropriate way and to allow themselves to feel anger and to see that as an indicator of where their needs or wants are not being met.

* Taibbi, Robert (2011), Doing Couple Therapy , Guilford Press, London